IS THE TCCWNA TIDE TURNING?

Last year this report observed, “Whenever there has been an opportunity for [New Jerseys] courts to crack down on victimless consumer lawsuits they have declined to do so.” So it’s quite nice to report that such an opportunity has finally been seized by the state’s high court.

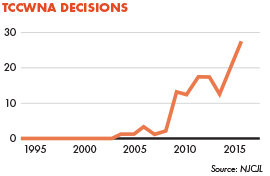

As documented at length in previous reports, a once obscure state law known as the Truth-in-Consumer Contract, Warranty and Notice Act (TCCWNA) has rapidly become a choice weapon for plaintiffs’ lawyers to attack businesses that sell products or services in New Jersey. Known as a “gotcha” statute,” the TCCWNA allows plaintiffs’ lawyers to bring class action lawsuits seeking $100 per violation—an amount that often greatly exceeds actual damages, if any—based on trivial technicalities, such as statements made on a business’s website that are inconsistent with a New Jersey regulation. Statements like, “void where prohibited,” for example, are a no-no. It doesn’t matter whether a consumer even read the terms or conditions, relied on them in making a purchase, or experienced a loss – it’s still grounds for a class action and a chance at big money for the plaintiffs’ lawyers running this racket.

As documented at length in previous reports, a once obscure state law known as the Truth-in-Consumer Contract, Warranty and Notice Act (TCCWNA) has rapidly become a choice weapon for plaintiffs’ lawyers to attack businesses that sell products or services in New Jersey. Known as a “gotcha” statute,” the TCCWNA allows plaintiffs’ lawyers to bring class action lawsuits seeking $100 per violation—an amount that often greatly exceeds actual damages, if any—based on trivial technicalities, such as statements made on a business’s website that are inconsistent with a New Jersey regulation. Statements like, “void where prohibited,” for example, are a no-no. It doesn’t matter whether a consumer even read the terms or conditions, relied on them in making a purchase, or experienced a loss – it’s still grounds for a class action and a chance at big money for the plaintiffs’ lawyers running this racket.

But in 2017 the New Jersey Supreme Court appropriately tapped the brakes on these out-of-control and often preposterous lawsuits. The court ruled that the failure of restaurants to list prices for every drink a customer might order on its menu should not subject it to a billion-dollar class action. Yes, that’s billion with a “b.”

During oral arguments the plaintiffs’ lawyer confirmed that under his interpretation of TCCWNA, the class action was potentially a billion dollar case. But the court was not persuaded. Its 5-1 decision in Dugan v. TGI Fridays and Ernest Bozzi v. OSI Restaurant Partners finally put some meaningful and much-needed limits on TCCWNA litigation.

The court began to bring some clarity to a critical element of the statute that requires consumers to have been “aggrieved.” It is not enough, the court found, for a business to have engaged in some trifling violation on paper. At the very least, the consumer must have seen that document, in the instant case, a menu. The court also held that the failure to provide prices on a menu does not violate a “clearly established legal right of a consumer or responsibility of a seller” as required under the TCCWNA because never before had someone made such a claim.

“Nothing in the legislative history of the TCCWNA … suggests that when the Legislature enacted the statute, it intended to impose billion-dollar penalties on restaurants that serve unpriced food and beverages to customers,” the court concluded as it denied class certification.

The ruling sets the stage for two more TCCWNA cases that are on their way to the high court: Spade v. Select Comfort Corp. and Wenger v. Bob’s Discount Furniture. Both cases involve claims that furniture sellers failed to include required language about timely delivery of furniture printed in 10-point type on contracts or sales documents, even as the consumers who sued received timely deliveries. New Jersey’s high court has agreed to answer two questions posed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. The first is whether a consumer who receives a contract that violates a state regulation is an “aggrieved consumer” even if he or she “has not suffered any adverse consequences from the noncompliance.” The second is whether a mere violation of the furniture delivery regulations, absent conduct that would otherwise violate New Jersey’s consumer protection law, violates a “clearly established right” under the TCCWNA.

Answering these questions should discourage the more outrageous, no-injury TCCWNA complaints that have clogged New Jersey court dockets in recent years.

As documented at length in previous reports, a once obscure state law known as the Truth-in-Consumer Contract, Warranty and Notice Act (TCCWNA) has rapidly become a choice weapon for plaintiffs’ lawyers to attack businesses that sell products or services in New Jersey. Known as a “

As documented at length in previous reports, a once obscure state law known as the Truth-in-Consumer Contract, Warranty and Notice Act (TCCWNA) has rapidly become a choice weapon for plaintiffs’ lawyers to attack businesses that sell products or services in New Jersey. Known as a “